I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder shortly before my 30th birthday. Acutely manic, powerfully overconfident, and terrified that medication or even stability would kill my creativity, I refused to take meds.

When I fell into a crushing depression a few months later, I realized that no matter what happened to my art (my passion, my livelihood, my identity), my survival depended on stability. Desperate, I succumbed, and set out into the dark, tangled forest of meds, blood draws, side effects, and big learning curves.

After a years-long arc of frustrations and triumphs, recorded in stacks of sketchbooks and journals, I found a tentative stability that became increasingly reliable. I wanted to make sense of that overwhelming tangled mess, and I turned to my art to shape my experience into a graphic novel.

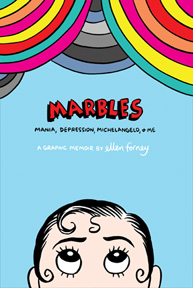

In January 2012, I turned in the final draft of Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me. It was a strange feeling: a combination of exhaustion, excitement and tremendous anxiety. I’d always been quiet about my bipolar disorder. What would happen when people found out? Would I be forever dismissed as crazy, untrustworthy? Would people be shocked? Would it be worse if they weren’t?

I learned something huge from putting my story out in the world: as I’d hoped, people told me I was giving them company, but I was given so much company, too. I was not a weirdo bipolar cartoonist specimen. Strangers, friends, readers, even interviewers would more often than not (I mean that) disclose their own personal experience with mental illness: their own diagnosis, their family history, their friend’s suicide, their son’s struggle. I didn’t know—couldn’t have known—how many chords my story could strike, or how many people were ready to be given an opportunity to come out.

Here’s the million-dollar question I get a lot: “Don’t you miss your manias?” The answer is very unsexy: “They’re not worth the risk.” No one asks if I miss my depressions!

My own, originally unexpected conclusion about being a crazy artist is that stability is good for my art. Mania was too distracting to get much work done and depression was too stifling. My current meds don’t pin me down, and a healthy lifestyle of regular sleep and good nutrition doesn’t rob me of my punk rock.

Stability is relative—I’ll always live with bipolar disorder, and I’ll always need to deal with that. My latest trick involves my blood draws, which, after all these years, I still hate: I buy myself a fancy tea drink afterwards. (My current favorite is Matcha Mint Mate Soy Latte.) Now when I’m on my way to the lab, I think about my fancy tea drink. Pavlov knew what he was doing. It works!

YOU HAVE COMPANY. TREAT YOURSELF NICE. And: DO YOUR ART!

Seattle cartoonist Ellen Forney’s graphic memoir, Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me, is a New York Times bestseller, with six foreign editions. She recently presented her work as keynote speaker at the Comics & Medicine Conference 2014 at Johns Hopkins Medical Campus.

marblesbyellenforney.com

http://www.graphicmedicine.org/comics-and-medicine-conferences/2014-baltimore-conference/

Images from Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me by Ellen Forney (Gotham/Penguin, 2012).